I was the only one in line for honey that morning at the Santa Fe Farmers’ Market. I found out why when I asked the young lady whose long braids were the same color as the stacked honey jars, how much for a quart. “$30,” was her reply. Stung by her answer, I replied, “Wasn’t it $25 last year?” “Yes, but we raised our prices.” I felt hot flashes coarse through my limbs; my throat went dry. Was this male menopause or a moral crisis induced by my eroding confidence as a committed local foodie? With trembling hands, I passed the cash to the sweetly smiling lass.

Things went from bad to worse when I moved to the egg farmers. I bought my usual large dozen from the Cruz Ranch stand and waited for change from my $10 bill. Geronimo, one of the ranch’s workers staffing the stand that day, looked at me quizzically. “They’re $10 now,” he said pleasantly. “Yikes! Is your boss getting greedy?” was all I could say.

When I caught up by email a few days later with the farm’s owner, Randy Cruz, I accused him of price gouging. Since we have a totally amicable, mutually insulting relationship, he fired back,

“I have to run a business and everything has gotten very expensive. I no longer do the farmers markets myself. I have to pay for someone [Geronimo] to be there. Gas is expensive, car insurance just went up again. Product liability insurance went up. alfalfa prices went up. Grains are up. Electricity is up. I use to pay 700 a month now 1200 a month. Vehicle maintenance. I just ordered 1600 new baby chicks for February [that cost] $5439.00; one year ago it was $2400! Baby duck [are] $4000! Sorry mark but I am running a business. Check out grocery store prices. Things have really gotten very expensive. You have a good night. Randy.”

The omelet I had the following morning had a bitter taste.

I left the farmers’ market with a much-lightened wallet, clutching my honey and egg purchases hard to my chest to discourage would-be thieves from stripping me of these treasures. My cognitive dissonance was so intense it roiled my innards. Yes, I wanted to support the local farmers, but why was I experiencing so much price point pain? In hopes of resolving the conflict, I decided to investigate the underlying economics and conduct area price comparisons.

To aid me in my research, I consulted with two noted agricultural economists, Dr. Buzz and Dr. Cluck, the former outstanding in his meadow and the latter highly regarded in her coop. They both reminded me that rather than being anomalous food products that consumers can do without, honey and eggs have attained exalted seats at America’s table. Pointing to work he’s done as the first actual bee appointed by the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture to the National Honey Board (“I had lived experience,” Buzz said, winking at me with one of his five eyes). According to Buzz and the Board, 2021 U.S. honey consumption was 618 million pounds, an all-time high surpassing the previous record of 596 million pounds in 2017. Currently, that puts per capita consumption at 1.9 pounds, up from 1.2 pounds in the 1990s. I confided proudly to Buzz that my personal consumption was about 5 pounds per year, well above the national average, which seemed to bring small tears to his eyes. Likewise, Dr. Cluck informed me that eggs were a big part of our diet with the average American eating 278 eggs per year, or about 6 a week.

To aid me in my research, I consulted with two noted agricultural economists, Dr. Buzz and Dr. Cluck, the former outstanding in his meadow and the latter highly regarded in her coop. They both reminded me that rather than being anomalous food products that consumers can do without, honey and eggs have attained exalted seats at America’s table. Pointing to work he’s done as the first actual bee appointed by the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture to the National Honey Board (“I had lived experience,” Buzz said, winking at me with one of his five eyes). According to Buzz and the Board, 2021 U.S. honey consumption was 618 million pounds, an all-time high surpassing the previous record of 596 million pounds in 2017. Currently, that puts per capita consumption at 1.9 pounds, up from 1.2 pounds in the 1990s. I confided proudly to Buzz that my personal consumption was about 5 pounds per year, well above the national average, which seemed to bring small tears to his eyes. Likewise, Dr. Cluck informed me that eggs were a big part of our diet with the average American eating 278 eggs per year, or about 6 a week.

Even though the US is second to China in total honey consumption, we only produce about a quarter of our own needs. Surprisingly, at least to me, North Dakota is the leading honey producing state with 33 million pounds in 2019, followed closely by their neighbor, South Dakota, with 19 million. That made me happy to hear that such “red states” were capable of producing so much sweetness. Argentina, India, Canada, and Mexico are among the largest honey exporters to the US.

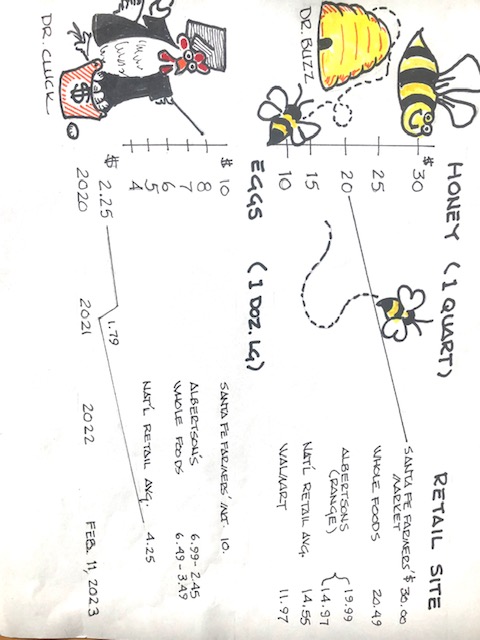

With growing demand and a relatively stable honey supply US retail prices have risen moderately over past years to about $6.00 pound. This translates to about $18.00 per quart (it takes 3 pounds of honey to fill a quart jar). But as one can see from the graph that Drs. Buzz and Cluck have assembled (they apologized for their graphic—in spite of Cluck’s “hunt and peck” technique their appendages make it difficult to use a keyboard or mouse) * prices were all over the map. As one might expect, retailers with high-price reputations sold honey, including locally produced, at higher prices than those with low-priced reputations.

But even Dr. Buzz was nearly swarming over the high-priced farmers’ market honey. When I asked him for his thoughts, he suggested that it’s often typical for farmers’ market prices to be higher than other retail outlets since they are made up of smaller producers with higher per unit costs. I did note that I bought honey at New Mexico farmers’ markets for $20 and $25 per quart in 2022, but even with inflation, it was hard to justify a price today that was 60 percent higher than the national average.

Sensing my overheated state, Buzz vibrated his wings so fast that I cooled down, then he explained that local market conditions—supply and demand, the relative affluence of an area’s shoppers—strongly influenced those prices. There are other concerns as well that sometimes drive price variations. Buzz, who self-identifies as a social and environmental justice worker bee, couldn’t conceal his anger over the millions of his brother and sister bees that die every year from such events as colony collapse disorder. This has been associated with environmental factors such as neonicotinoids, a class of insecticides, and climate change. “You humans are biting the hand that feeds you!” he pronounced reminding me that one-third of the U.S. diet is derived from insect-pollinated plants.

The whole time Buzz and I were talking, Dr. Cluck was listening intently, affirming his remarks with repeated scratches in the dirt. “I, too, have seen millions of friends die over the past year, in our case from avian flu—58 million poultry birds including 43 million laying hens—the worst animal disease outbreak in US history. Those deaths are hard to take.” As my friend Randy’s rant confirmed, the high price he’s paying for replacement birds is a result of the flu and is one of a litany of reasons for elevated egg prices.

With ruffled feathers, Dr. Cluck said, “Humans give us a hard time. They wisecrack, ‘What’s the matter? You on strike? Why aren’t you laying more eggs? Isn’t the regular chicken feed good enough for you? You need the fancy organic stuff?’” Visibly agitated, Cluck screeched, “We’re not machines; we can’t just pump out more eggs at the push of a button!”

From my investigation, egg prices, like honey varied widely depending on where they were purchased and their respective claims to such attributes as organic, natural, cage-free, nothing artificial, pasture-raised, or just every day industrial eggs. But no matter how you pluck it, the base price of eggs has gone up 211 percent over the previous 12 months with the national average peaking in early February at $4.25 for a dozen large eggs. I did, however, find cheaper eggs at Albertson’s and even Whole Foods. And then there were the “golden eggs” at the farmers’ market.

Expressing my exasperation with the price of locally grown food, I told Cluck that I could get two-and-a-half Egg McMuffins at McDonalds with just the money I’d save from buying the cheapo, non-farmers’ market eggs. “Yes, but you are one of those rare birds, a special breed of values-driven shopper who will patronize a farmers’ market because you feel it’s the right thing to do,” she replied, comforting me with her soft wings.

Cluck was right. I rationalize that paying more now—though not in my short-term best interest given the available lower cost options—has numerous long-term benefits. I even confessed to not making tax deductible donations to the farmers’ market nonprofit partner because I know that I’m paying the farmers significantly more than I would by shopping at conventional outlets. Though no portion of my “farmers’ market premium” payment is tax deductible, I know I’m supporting local farmers who, as the pandemic proved, came close to being the last line of defense when national supply lines were disrupted. In other words, I see the larger project of buying local as an insurance policy against catastrophes that are now occurring more frequently, and may in fact be related to the industrial food system’s unsustainable model of food production. “The chickens are finally coming home to roost,” is how Cluck put it, though even she wasn’t sure what that meant.

Local agriculture’s other benefits and virtues have often been extolled: it keeps the region’s farmland open and working; it contributes to diverse local economies; it supports aesthetic values associated with open space and nature; it sustains centuries’ long cultural and agricultural traditions; it’s essential to protecting and enhancing food security and sovereignty. And to the extent that today’s high egg prices are associated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the disruption of grain supplies, then they should be regarded by us as a small price to pay for the sacrifice Ukrainians are making to oppose the iron fist of authoritarianism.

If I had a quarter, however, for every time I said “WTF!” when looking at farmers’ market prices, I could actually afford that food. But as Drs. Buzz and Cluck so carefully instructed me, there’s a deeper and more complicated story behind my sticker shock, a story that links local to national to global; a thread that connects us to the environment, labor, and land; and a potentially tragic tale of how humankind harms the animals it depends on.

It might be wise to see these price signals not as a reason to go running for the shelter of Walmart’s bargain basement prices, but as signs of looming threats to our self-induced vulnerabilities, ones that are finding ways to reveal themselves ever more frequently. The time has come to heed the facts of life as told by the birds and the bees.

*A special thanks to good neighbor Jack McCarthy for his artistic acumen.

Sources:

- All honey and egg prices, except for national averages, are from a survey conducted in Santa Fe, New Mexico on or about February 11, 2023

- New York Times (February 3, 2023) Why Eggs Cost So Much – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

- USDA, National Honey Board, “USDA Reports Demand for Honey Reaches All-Time High,” (August 17, 2022)

- USDA, National Honey Report, Volume XLIII – Number 1 (January 25, 2023)

- USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service, (March 19, 2020)

- “The Bird Flu Outbreak Has Taken an Ominous Turn,” The Bird Flu Outbreak Has Taken an Ominous Turn | WIRED

well done – explanative and almost funny