Yes, I’m from New Jersey. After years of therapy, I now proudly and openly embrace the place of my birth and coming of age, both for its physical attributes as well as its hard-earned state of mind. With that acceptance, of course, comes an acknowledgement of its contradictions. The much-coveted Jersey Shore and lush Pine Barrens stand in stark contrast to the refineries of Bayonne and the state’s contorted roadways, site of many of America’s most legendary traffic jams. Celebrities like Sinatra, Springsteen, and Streep inspire and move us, while Jersey’s corrupt politicians such as former U.S. Senator Harrison Williams and Camden Mayor Angelo Errichetti (the inspiration for the movie “American Hustle”) repel us. Perhaps it’s because of this history and its inconsistencies that I feel a bit nonchalant about the recent indictment of NJ’s U.S. Senator Bob Menendez on bribery charges. After all, why shouldn’t a guy be allowed to walk around with a little gold bullion in his pockets? You never know when you might need a pack of gum or to feed a parking meter.

Yes, I’m from New Jersey. After years of therapy, I now proudly and openly embrace the place of my birth and coming of age, both for its physical attributes as well as its hard-earned state of mind. With that acceptance, of course, comes an acknowledgement of its contradictions. The much-coveted Jersey Shore and lush Pine Barrens stand in stark contrast to the refineries of Bayonne and the state’s contorted roadways, site of many of America’s most legendary traffic jams. Celebrities like Sinatra, Springsteen, and Streep inspire and move us, while Jersey’s corrupt politicians such as former U.S. Senator Harrison Williams and Camden Mayor Angelo Errichetti (the inspiration for the movie “American Hustle”) repel us. Perhaps it’s because of this history and its inconsistencies that I feel a bit nonchalant about the recent indictment of NJ’s U.S. Senator Bob Menendez on bribery charges. After all, why shouldn’t a guy be allowed to walk around with a little gold bullion in his pockets? You never know when you might need a pack of gum or to feed a parking meter.

Aside from its dubious distinction of maintaining a high occupancy rate in the “Jersey Wing” of the Federal Penitentiary, the Garden State’s most significant contribution to the world just might be the tomato. As a boy, it’s the first vegetable (I know it’s a fruit!) I fell in love with after seeing plump red clusters swaying seductively on the vines of my neighbor’s backyard garden. Due to its unique configuration of humidity, temperature, and soils, New Jersey, which is essentially a peninsula, produces the most flavorful tomatoes, aided by the tender and knowing hands of Rutgers University (the State University of New Jersey) plant scientists.

I can hear your groans after reading such a smug assertion. California, Florida, Ohio—you can strut your stuff and make all the noise you want, but I’m prepared to defend my claim with a duel, a means of settling disputes which I believe is still legal in New Jersey. With a bushel full of just-picked, peak of harvest Jersey tomatoes by my side, I’ll challenge all comers to meet me at the toll booths off exit 9A on the New Jersey Turnpike. We’ll each grab one of our respective tomatoes, and standing back-to-back, take 10 strides in the opposite direction, turn and heave it at the other. Yours may strike me directly in the chest; though knocking me back a foot or two, it will bounce off and skid harmlessly down the pavement like a tennis ball. Mine, on the other hand, should it land as intended on your forehead, will splatter luxuriously across your face leaving rich, red trails down your cheeks, flowing into your gaping and eager mouth. Your eyes will open wide, a smile will grace your lips, and New Jersey tomato nirvana will descend upon you.

The Tomato

As good as the many varieties of tomatoes grown in New Jersey are, they face the same limitation as any other fruit or vegetable grown in a temperate zone—seasonality. Whether I’m nursing them along in my New Mexico garden, or a large commercial farmer is producing them for fresh market, you’ll be lucky to get eight weeks of respectable, locally grown fresh tomatoes a year, even with the benefit of season extenders (don’t talk to me about greenhouse tomatoes or winter tomatoes shipped thousands of miles—they are only useful for batting practice). My personal “season extender” is canning, which when it comes to tomatoes is easy to do in just about any home kitchen. All you need is a large pot for boiling water and a few glass canning jars with lids and tops. I’ll produce enough surplus tomatoes from my garden, sometimes supplemented with 5 to 10 pounds of “seconds” from the farmers’ market to meet my processed tomato needs for a year.

That’s good for my basic cooking needs, but what about that essential tomato sauce for pizza, a menu item so ubiquitous that it seems to be available in every eatery I go to these days (as they say in New Jersey, pizza’s not just for pizzerias anymore!). Or what about your favorite “date night” Italian restaurant whose marinara sauce is so good you’d hurl yourself through rings of fire for. And how about those poor souls whose craving for ketchup is so powerful, that French fries and hot dogs are no more than an expedient form of transportation. Without commercially available processed tomato products, these essential food and menu items would disappear, plunging our reason for living into doubt.

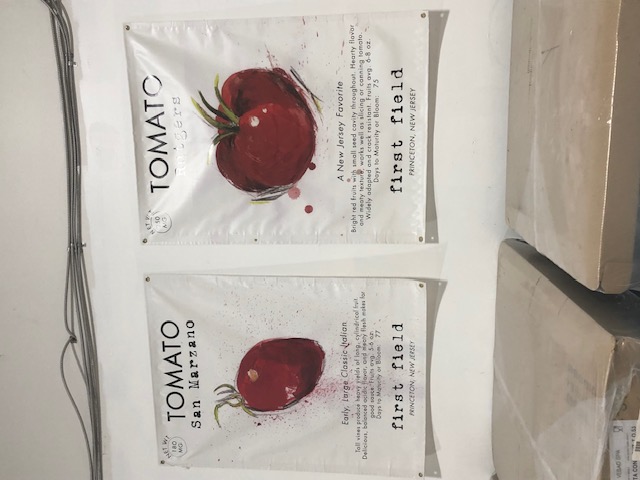

But what if you could have that Jersey tomato terroir year around, grown by local producers, processed by a small, family-owned business, with taste and quality second to none, distributed at scale to retailers and restaurants within a few hundred-mile radius, and available online to the rest of us who don’t have the privilege of living in or near New Jersey? Well, the good news is that you can, and it goes by the name of “First Field” First Field (first-field.com). The inspiration and passion for this food business comes from the decidedly non-corporate couple, Theresa Viggiano and Patrick Leger. Together, they spawned a mom-and-pop start-up which transitioned into a fast-growing food processing business that stakes its reputation on the authenticity of “Jersey Grown” and their working relationship with growers and buyers.

First Field

Like many young farmers and food entrepreneurs today, Patrick and Theresa don’t have deep agricultural roots. Theresa is a “Jersey Girl” who was doing graduate work at Rutgers on aging and mental illness but always had a passion for gardening. Patrick grew up in North Carolina, earned an MBA at Vanderbilt, but was born in Quebec which, interestingly, gave the couple their only food processing cred. “We eat more ketchup in Canada per capita than anywhere in the world. We put it on everything,” he tells me. So armed with his mother’s homemade ketchup recipe and a bumper crop of tomatoes at their Jersey homestead in the summer of 2013, they made their first batch of ketchup.

You might say the rest is history. Like a garage band that got its first gig at the local VFW hall and then moved on to play stadiums, the couple started selling their backyard tomatoes and ketchup off a card table at the foot of their driveway with a cigar box for honor payments. Today, First Field’s crushed tomatoes, marinara sauce, ketchup, cranberry sauce, and pumpkin puree have elbowed their way onto the shelves of some of the region’s most prestigious retailers like Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s. Their sauces are gracing the pies of some of the best pizza restaurants in New York City, including the Andrew Bellucci (aka “The Don of Dough”) Pizzeria in Queens. “They like our sauce because it’s rich. Pizza dough doesn’t like watery sauce!” says Patrick. And their success to date has meant that some of the country’s biggest food retailers and service companies are knocking at their door.

In spite of its modest success–annual sales are growing rapidly—First Field is not a rag to riches story, nor does it evoke the purest sentiments of the local food movement. Again, like family farms where at least one member of the household works a non-farm job, Patrick works as a full-time investment advisor, the income from which supports the family (they have two children, ages 8 and 11). Theresa directs the business on a very full-time basis while Patrick fills in with finance and operational work in the evenings and on weekends. Though they have been in business now for a few years, neither one of them takes a salary. This reflects their desire to effectively self-finance the start-up with money from family, friends, and even Equal Exchange, the worker coop and fair-trade organization that has been expanding their line of domestic products. Patrick and Theresa did take one major step forward in the direction of self-care this summer: they took their first two-week vacation since the business began.

The keeping it close to hearth and home approach is as much a rejection of the usual start up finance model that relies on venture capitalists, or even a bank with more progressive lending practices, as it is a fervent desire to keep their lives family-focused and ultimately sane. An unstated company policy is that family comes first. That’s why the first thing you see when you walk into Food First’s modest facility, located in a non-descript commercial business park in central Jersey, is a large day care space that also served as a kind of one-room schoolhouse during the Covid-19 lockdown. To the same end, Patrick and Theresa would probably acknowledge that their most important off the books’ “assets” are Theresa’s Jersey Shore parents who provide exceptional grandparenting services.

But one’s family values can still be put to the test. On the Sunday afternoon I visited their facility, Theresa was stirring a giant kettle of cranberry sauce to meet a holiday order from a customer (“Thanksgiving comes earlier every year,” she said with a sigh) while Patrick was stacking cases of pumpkin puree on a palette for shipment to a pie baker in Boston. Besides the two of them, they have three other full-time employees with a fourth expected to start that Monday. In all likelihood, Theresa’s grandparents were supervising the construction of sandcastles on one of the Shore’s waning summer days. When the harvests start cascading off the farms, and the customers say they want what they want now, you don’t pack your sunscreen and head for the beach.

Getting ahead while keeping your head may be one of the most challenging facets of any business. But staying true to your mission, i.e., a set of values that drive your business, while managing the food system’s many headwinds is both an art and a science. Like other idealistic foodies, Patrick and Theresa set off with the hope of controlling every aspect of their supply chain and staying within a well-defined organic lane. They received assistance from the Rutgers University Innovation Center to learn the food processing trade and then piloted their product development at Elijah’s Promise, a non-profit job training and community soup kitchen in New Brunswick, NJ. Elijah’s Promise gave them a chance to use a commercial kitchen after hours (“we were the night shift,” joked Theresa) to hone their production skills and earn their FDA approval.

Again, with guidance from Rutgers Cooperative Extension, they headed out into the field to find local farm product suppliers. This is where their ideals and early assumptions started to bump up against reality. Hoping to buttress their brand with a strong organic identity, they soon realized that New Jersey’s organic growers didn’t have sufficient production to meet First Field’s demand. Similarly, the growers were small and often producing different tomato varieties. When you’re canning commercially, you can’t mix ‘n match nor throw whatever’s coming off the field into your #10 can. Product performance and consistency are sacrosanct for chefs.

When they talked to conventional tomato growers who were large enough to supply them, “we realized that we were being starry-eyed greenies,” said Theresa. In other words, no farmer could get over the high bar they were setting; they were clearly at a crossroads. As Patrick put it, “We had to decide if we wanted to be organic—sure, we could have imported organic tomatoes from Mexico—or did we want to support local.” Though New Jersey’s 26 or so commercial scale tomato growers had consolidated down to 6 over the past couple of decades, there are thousands of acres of prime New Jersey farmland comprised of well-drained, sandy loam soils producing highly regarded tomatoes for both fresh slicing and canning markets. To the chagrin of the state’s organic farming community, First Field chose local commercial scale producers as the most feasible path for their business. According to Patrick, this required them to work harder to build working partnerships with organic farmers over time. This has resulted in First Field’s commitment to buying other produce like winter squash, cranberries, and blueberries from small, local farmers to supply the 25 percent of their business that is not tomato based. “Building trust with all our farmers—big and small—is the most important thing we do. We can’t just show up one year and not the next. We have to prove we’re real year after year after year,” said Patrick.

Tomato Land

The New Jersey Turnpike is essentially a northeast region tomato corridor in the middle of one-quarter of the nation’s population. The state’s farmers are growing vast quantities of tomatoes (some fields are only one hundred yards from the Turnpike), going to canneries in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, or elsewhere, and then onto the warehouses that serve the wholesale and retail supply chains. In choosing to support local growers and the Jersey identity that goes with it, First Field also chose the one remaining tomato cannery in New Jersey to process and pack their tomatoes. It is owned by a large food conglomerate. According to Patrick, their dream would be to one day have their own cannery and avoid the potentially volatile world of large food corporations. At the moment, their other non-tomato canning takes place at their central Jersey facility.

New Jersey may be a tomato corridor, but it’s also the most densely populated state in the country. Land values and development pressure are enormous, but even with New Jersey’s Department of Agriculture’s courageous efforts to protect farmland, the dike can only hold for so long before the rising waters of sprawling subdivisions bust it loose. As a public policy tool, farmland preservation efforts are really just an interim measure; ensuring that farmland remains working land requires that it’s not just protected from the rapacious condo kings, but that it also performs within the parameters set by the food system’s marketplace. To that end, First Field is the tip of the market innovation spear. Using the “Jersey Fresh” logo, telling the local Jersey story on their cans and jars, but perhaps most importantly, proving through the quality and performance of their products that Jersey grown is something more than advertising schmaltz. Rob Everts, a co-director of the fair-trade leader Equal Exchange put it this way: “First Field is an excellent example of a small, socially and environmentally driven business trying to rebuild the New Jersey tomato industry in a truly sustainable way. We are so inspired by what they are doing that we have invested in their business to try to ensure its success.”

The consequences of First Field’s success or failure are enormous. Without robust regional connections between farmer, processor, buyer, and eater—ones that are geographically close, not based on cross-country or global shipping—Jersey growers may not be around in 10 years. As Patrick put it, “That would be like paving over Napa Valley. It would be an incredible shame!”

The Seed

Cut into a ripe, red tomato and let the pulp and juice pool up on your cutting board. Carefully separate out some seeds with the tip of a knife and push them to the edge for a few minutes to dry. Select just one by pressing a finger tip gently to it so that it sticks to your skin. Examine it closely and measure it. With my crude measuring instrument, I determined that a single oblong seed from one of my homegrown tomatoes was 3/32nd of an inch wide and 1/8th of an inch long. Inside that tiny hard body doesn’t necessarily rest the secrets to the universe, but it’s pretty darn close. From my 2023 Johnny’s Selected Seeds catalogue, I could choose from 103 separate tomato seed varieties, the description for each one touting their unique attributes related to size, shape, color, taste, slicing, saucing, selling, and much more, none of which you’ll detect by simply looking at the seed. The one attribute that most varieties shared, including the one stuck to my fingertip that would blow away if I exhaled too hard, is their capacity to produce a large green plant that could, if tended correctly, set 5 to 10 pounds of edible tomatoes. In spite of a passing understanding of the science behind all of this, I still regard that itsy-bitsy thing resting on my pinky as a miracle for its ability to produce a nearly infinite variety of characteristics.

At Rutgers University, miracle and science have found a happy partnership. The original Rutgers tomato, which Wal-Mart refers to as the “Legendary Jersey Tomato,” may have indeed been handed down to humankind by the Creator, but its infinite refinements and applications for multiple purposes and settings is decidedly secular. And for large tomato growers who are spending upwards of $20,000 a year on seed, getting the right variety for the right purpose at the right time is crucial.

First Field has a similar interest. If the tomato their canner turns into sauce only succeeds in creating a runny pool atop a beautifully hand-thrown pizza crust, a string of Italian, Spanish, or Haitian-Creole accented expletives will ensue. First Field’s phone number will disappear among the salami rinds. That is why they are working closely with Rutgers Professor Tom Orton whose name is spoken with hushed reverence by Patrick. Professor Orton, responsible for the “Rutgers 250” that was written up in the New York Times, is now collaborating with First Field to create the perfect sauce tomato that, in turn, will be perfectly suited for South Jersey growing conditions.

Patrick breaks it down for me this way: “A tomato that is too watery will take longer to cook down which uses more energy and robs the tomato of its flavor. We are working with growers to set aside small plots of their land for seed trials. That’s one way we’re collaborating with our producers.” Keep in mind that none of this “seed work” uses genetic engineering (no one’s crossing a San Manzano canning tomato with a bunny rabbit). Finding the right processing tomato is a glacial process requiring years of diligent lab and field work, but it is no small part of saving Jersey farmers, farmland, and a big chunk of the Northeast food system.

To make the point clear, Patrick brings out a 3-feet by 4-feet wood frame with one side covered in a fine wire mesh screen. Three separate groups of about two hundred seeds each lie on the screen. He explains to me how each group contains certain desirable traits that the wizard Professor Orton will combine to bring to fruition, that will in turn be selected for their desirable traits, and so on. I think back on that one, minute specimen perched on my fingertip. Like Henry David Thoreau, I have “a faith in the seed” that, if this whole process is handled correctly, New Jersey might play a big part in saving us from a global food system controlled by a few giant corporations.

The Taste of Liberation

Patrick is fumbling around their makeshift office kitchen for a spoon so that I can sample their sauce. With a little grunting, he opens up a #10 can of crushed tomatoes with one of those little manual butterfly can openers that your grandmother used. I scoop up a spoonful, then another, and swirl it around my palate. This may be the first time in my life I’ve eaten tomato sauce straight out of a can, but soon I’m contemplating it the way I might a good Bordeau. Do I sense something rich, earthy, even chunky though the sauce is smooth as silk? Calling upon my limited wine tasting vocabulary, I wonder if I’m savoring notes of New Jersey in this robust red pulp. I realize, in fact, that the joy prancing across my tongue isn’t just from the flavor bequeathed to the tomato by my home state’s soils, clammy summers, and the rigorous seed massaging of plant scientists. It’s a taste of liberation from a dominant food system that only wants to treat you like a semi-conscious consumer and raw food products like they are no more than commodities. First Field is what the alternative tastes like.

An excellent thought provoking article, Mark. Thanks for it . . . It made me consider what is the appropriate business model for local food enterprises? For example, while building a community of local tomato farmers that would enhance NJ Ag, First Field is seemingly focused on distant, as well as local, markets, as critical to their economic success. Wouldn’t a more sustainable business model focus on a more limited distribution goal to control their C Footprint, as well as act in solidarity w/ other locally-sourced Food Enterprises that similarly want to contribute to their local Ag market potential? Yes, I’ll visit that Queen’s pizzaria when I go to NYC to experience the wonderful flavor of their tomato sauce but I still want to have access of foods that celebrate the richness of dryland farmed tomato products when visiting CA and/or the Slow Food Ark of Taste tomatos when in South Carolina. I just think that local/regional markets are a crucial part of local food systems.Thanks.