(This is the second in a two-part series that looks through a food lens at two New Jersey towns—Paterson and Ridgewood—that are only a few miles apart geographically, but light years apart socio-economically. Part I focused primarily on Paterson, while Part II will focus on Ridgewood, my hometown.)

“The province of the poem is the world.” “Paterson” by William Carlos Williams

Former site of the Ridgewood Grocery Coop and the author’s first job.

Ridgewood is a town of 25,000 people located in Bergen County, whose eastern border looks across the Hudson River into northern Manhattan. Based on what I thought I knew about the place where I grew up, the expectations I had for Ridgewood were a redundance of abundance, all the perks that privilege can lay claim to, and a surfeit of greenery and scenery. I wasn’t disappointed. But beneath the enchanting display of its idyllic downtown and serene suburban neighborhoods, Ridgewood’s residents rarely rise to the level of conspicuous consumption, adhering instead to unspoken principles of tastefulness and understatement.

While wandering around Van Neste Square—as pleasing a little town green as you’ll find anywhere—I chatted with two bored police officers propped up against their patrol cars. Joking with them about when they expect the next crime wave to hit, they smirked, then cracked that they had just issued warnings to a couple who were out of compliance with the town’s dress code. With mock indignation, I asked them what they were going to do about the young man asleep on a bench at the far end of the park? “Ah, he’s not hurting anybody,” they replied.

Having just come from Paterson, where only 10 days prior to my arrival eight people were shot in one night (none fatally), I was grateful for the sense of safety the village afforded. But just to confirm I wasn’t missing a carefully concealed cauldron of murder and mayhem, I checked the crime statistics. On average, Ridgewood’s violent crime rate, according to Crimegrade.org, is 0.75 per 1,000 residents earning it an A+ safety rating from this site. Paterson, on the other hand, has 3.73 violent crimes per 1,000 earning “The Silk City” a C- rating.

“War! a poverty of resource. . . “ “Paterson”

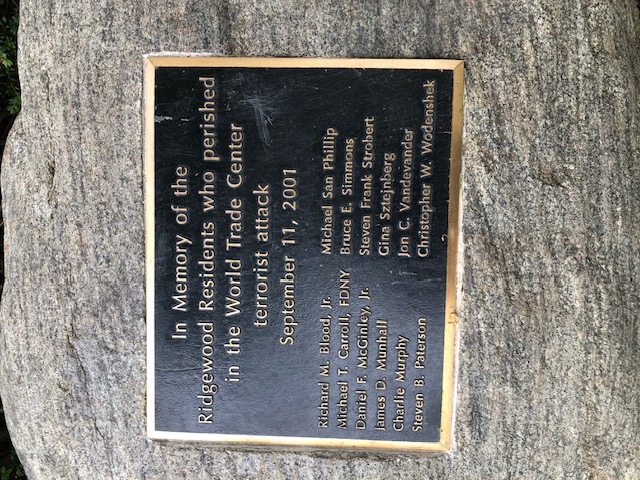

Ridgewood citizens lost in 9/11

Though I paint a picture of a place encased in a bubble, even affluence doesn’t keep you from harm’s way. On the park’s westside is the war memorial that records the sacrifices the townsfolk made to humanity’s bellicosities, including my generation’s big mistake. The Vietnam War took 11 Ridgewood boys, my peers, a loss I’m likely to never forgive this nation’s leaders for. And on an inconspicuous boulder wrapped in shrubbery sits a plaque memorializing 12 Ridgewood citizens whose souls left this earth on 9/11 as the Twin Towers fell to the ground.

But as the person returning to the place that’s largely responsible for who I am, I had to pay my respects to some of the sources of my food stories. Just a hop, skip, and a jump over the railroad tracks from the park is the former site of my first real job—a cooperative supermarket, the last of the pre-granola “old wave” grocery coops that once dominated Main Streets everywhere. Guess what’s there now? A Whole Foods, whose parking lot couldn’t squeeze in another BMW if it had to. As a bag boy for the site’s earlier retail food incarnation, I sent many an egg to an early death by packing the cartons in the bottom of the grocery bag.

Just over half-a-mile from Whole Foods is a Stop & Shop supermarket, where those of more modest means secure their victuals. It was formerly a Grand Union before that chain’s regional identity was forever lost to a wave of corporate raiders who picked over their acquisitions and sold them off for parts. But Ridgewood’s underlying wealth gave this store a second life, albeit under a different name. If you add in a few lesser supermarket retail brands just over the borders of neighboring towns, Ridgewood is a shimmering food oasis when compared to Paterson’s food desert status—officially determined to be the 13th (southside) and 15th (northside) worse food deserts in New Jersey.

I started motoring “uptown,” which is barely a few blocks west of downtown, where I soon passed my former elementary school. What’s notable about my tenure here in the early 1960s was the total absence of a school meal program, perhaps because we all had stay-at-home moms. This forced most students, including myself, to walk home for our so-called lunch period which was an hour in length. A 19-minute walk home, followed by 19-minutes inhaling a Fluffernutter sandwich and a glass of milk, and a 19-minute return walk gave me exactly 3 minutes of playground time before school resumed. Not that anyone was paying attention to empty calories back then, but given that I was walking or biking four miles to and from school each day—morning, noon, and afternoon—I could have been getting a steady IV drip of Fluffernutters with no ill effects.

Formerly The Corner Store and site of the author’s early adolescent candy addiction.

In a similar vein, I had to track down a former den of nutritional iniquity that was only a few blocks from my house. I found my way up North Monroe Street until I took a left onto West Glen Avenue. At that intersection is a small park where my pals and I spent countless hours throwing, hitting, or kicking whatever ball happened to be in season at the time. Our considerable exertions, to say nothing of our astounding acts of athleticism, earned us the right to indulge the treats available at the nearby Corner Store that I was now searching for. Having heard rumors of its demise I was guessing it was gone. To my delight, it was still there—barely signed, no bigger than it was in 1956, and now operating under the name of Park Wood Deli.

I entered the premises with only slightly less reverence than when I once entered Chartres Cathedral. No longer a general grocery store where my mother often sent me at the age of 12 with a one-dollar bill and signed permission note to buy her a pack of Salem cigarettes, it now sparkled with display cases of prepared take-out food. Gushingly, I told the young clerk that this was the place where I came with friends 65 years ago to buy candy, soda, and fruit pies after our ball games. We’d sit outside, against the store’s front wall and consume our “contraband” with gusto. (I can say with a limited degree of certainty that 75 percent of the ultra-processed food I’ve eaten in my lifetime was ingested against that wall). The clerk smiled, and with only a hint of condescension said, “That’s nice to hear, sir; you know what, they still do that,” pointing out the window at the same spot. And wouldn’t you know it, exiting the store just ahead of me, sheepishly clutching similarly illicit items were five boys I guessed to be about 12-years old. Single file, they lined up, backs to the wall, and slid down its smooth surface in unison until they sat on the sidewalk. Devoutly, they unwrapped candy and cakes, and popped their cans of soda.

Noting the irony of how one site of my misspent youth contrasted with my next destination, HealthBarn USA HealthBarn USA | Strong Bodies, Healthy Minds, I headed back up North Monroe for my appointment. This unique, for-profit organization, which provides a range of healthy eating and gardening programs for children and adults, had come to my attention a few months earlier. When I learned that it was located in Ridgewood, my first question was, why? In a place so affluent (the average household income is just shy of $200,000) and highly educated (78 percent of the adults have bachelor’s degrees or better), Ridgewood would be the last place (Paterson being the first) I would choose to place such a beneficial program. Though obesity and diet-related illnesses have cut a deadly swath across all income, race, and ethnic categories, rates are significantly lower for white and college-educated groups. That’s Ridgewood.

Approaching HealthBarn’s location, I drove along streets where the shade trees were so thick and lush you barely noticed the expensive homes the flora carefully concealed. I passed a natural pond with a small, cascading waterfall that ran under the road into a lower pond which turned out to be the southwest corner of Habernickel Park, the site of HealthBarn’s facility.

The public park, formerly a privately owned 10-acre horse farm, is a testament to Ridgewood’s capacity to secure much-needed open space in a town that is 99.9 percent built out. When the owners decided it was time to sell the property, the surrounding homeowners were seized by that paroxysm of fear the wealthy are heir to–a developer will carve out an obscene number of lots for a condominium complex! Quickly, the town, county, and state stepped in to calm jittery nerves by purchasing the land and its house for $7.4 million and turning it into Habernickel Park. When the dust settled in 2016, the modest house, an outbuilding, and an adjoining garden area were leased by Ridgewood to HealthBarn.

“BRIGHTen

The corner

where you are!” “Paterson”

Upon entering the premises, I was greeted by Stacey Antine, HealthBarn’s energetic and entrepreneurial founder. Standing in the foyer, I also found myself engulfed by swirling pools of chattering children who were called either “sprouts” or “seedlings.” I learned that the horticultural designations (later I would also meet “young harvesters” and “master chefs”) were based on the child’s age, which would then channel them into various activities, rooms, and adult leaders. All in all, it was the kind of camper/counselor, controlled chaos atmosphere that I recalled enjoying during my own day camp days.

HealthBarn USA’s children’s garden. Strawberries waiting for some spring warmth.

Amidst the commotion and the occasional wayward seedling uprooted from their pot, I sat down with Stacey to hear her story. Part of her motivation to establish HealthBarn in 2005 came when her father was battling cancer. “But the quote that got me hooked,” she tells me, “was ‘this is the first generation of children who won’t live as long as their parents’ generation based on lifestyle choices.’ When I heard that, I knew I wanted to be part of the solution.” Stacey got out of corporate marketing and started graduate work at NYU to pursue nutrition sciences and become a registered dietitian. Soon, HealthBarn was hatched as a child and family food enrichment program that competes with today’s plethora of non-school activities—athletics, ballet, tuba lessons; in other words, the haute-suburban culture that spawned the term soccer mom.

In addition to hands-on food and gardening programs, HealthBarn offers a summer camp and adult culinary workshops. Between the lovely setting and high-quality programming, HealthBarn attracts people from several nearby towns. As a for-profit business, however, these programs are not inexpensive. One week of HealthBarn’s summer camp is $720, and 10, 90-minute per week summer sessions for young children are $425. Scholarships are available, and Stacey makes a strong effort to raise money to support them, but clearly HealthBarn targets an upscale market.

HealthBarn USA’s business reality prompted Stacey, in part, to establish the non-profit HealthBarn Foundation in 2015 as a way to direct healthy meal services and funding to needy people. The foundation receives donations for the scholarships that underwrite the participation by lower income children in HealthBarn USA’s programs. It also offers a variety of special school nutrition education programs (coincidentally, earlier in the day that I visited HealthBarn, Stacey had provided a nutrition program to a middle school in Paterson).

But the service that really put the foundation on the map is Healing Meals. Described as “a nutritious food gifting program made with love,” it set out to provide special meals to ill children and seniors. As Stacey put it, “I wanted to go beyond just feeding people. I wanted to give people nutritious meals.” By placing quality ingredients and the highest standards of nutrition ahead of quantity and calories, the program developed a favorable reputation throughout Bergen County. In the course of providing meals to seniors, Stacey and her team discovered malnutrition in one of Ridgewood’s affordable senior housing facilities that did not offer an on-site meal service. In cooperation with Ridgewood Social Services, Healing Meals began preparing meals for those seniors who were just barely getting by. This burnished their image further, but more importantly, it prepared HealthBarn for the big bomb that exploded across the U.S. in March 2020.

There is the story of the cholera epidemic and

the well known man who refused to bring his

team into town for fear of infecting them

but stopped beyond the river and carted his

produce in himself by wheelbarrow – to the

old market, in the Dutch style of those days.

“Paterson”

COVID-19 and the lockdown that followed set off a rapid chain of events in the food world. Under the auspices of Ridgewood Social Services, Healing Meals immediately ramped up preparation to 150 meals a day for Ridgewood’s isolated COVID-19 shut-ins. With the HealthBarn programs for children and families shut down, Stacey turned her attention to feeding those in need, a number that was growing by the day, and often under very challenging circumstances. For instance, the staff at Ridgewood’s Valley Hospital was not only struggling to keep up with the surge of patients, but its exhausted staff also needed to be fed. Ridgewood’s then-mayor, Ramon Hache, saw the opportunity to solve two problems at once, the second being the downtown restaurant community that was shut down and laying off large numbers of lower-income workers.

Mayor Hache connected with Paul Vagianos, the proprietor of one of those restaurants, Greek Like Me, and together, under the auspices of the Ridgewood Chamber of Commerce, kicked off Feed the Frontline to mobilize Ridgewood’s restaurants to feed hospital workers. They needed two more things, however: a nonprofit sponsor to receive donations, and the donations themselves. Stacey’s HealthBarn Foundation solved the first problem, and the people of Ridgewood solved the second. In a one-night social event for Ridgewood Newcomers, $13,000 was raised. Over another week or so, an additional $100,000 came rolling in. Everybody was stunned by how fast Feed the Frontline came together. As Stacey told me, “Ridgewood came through like you wouldn’t believe! Pretty soon, we were operating like a well-oiled machine.”

That was only the beginning. Yes, Ridgewood had the resources and the generosity to take care of its own; its downtown restaurant scene was a destination eatery for all of Bergen County, sporting about 50 restaurants throughout the town, 38 of which were highly rated by TripAdvisors.com. But looking beyond the village’s boundaries, COVID was churning up a world of hurt. According to the Bergen County Food Security Task Force, the county had 104,000 food insecure people. How would they be fed when people were losing jobs and the food pantries were shutting down?

Hache, Vagianos, and Antine conspired to take Feed the Frontline to a higher level. Less than two months into the lockdown, the New Jersey Economic Development Authority launched their Sustain and Feed initiative as a way to meet the rising tide of hunger across the state. Stacey, who had not written a lot of government funding applications before, decided to tackle the state application that offered grants ranging in size from $100,000 to $2 million. Being cautious, she thought she’d only aim for $100,000, but then, “I said to myself I don’t think that’s enough, so what the heck, I’ll just add another zero to kick it up to $1 million. I was totally shocked when we got it!”

With a large infusion of state bucks, the Ridgewood Sustain and Feed initiative went into high gear. Vagianos and Hache brought 20 of the town’s struggling restaurants into the fold, and together they started pumping out 1,000 to 2,000 prepared meals a week that were going to needy households identified by local food pantries all across the county. Initially, the state reimbursement rate was $10 per meal, later bumped up to $12, but hardly approaching the kind of revenue that restaurants with $40 menu entrees were used to getting. Nevertheless, it kept them afloat and, perhaps more importantly, it kept their lowest-paid workers employed.

Of course, preparing the meals and identifying the recipients is one thing; delivering them safely to the right place and person is another. That’s where Ridgewood showed its stripes again. Over 400 volunteer drivers emerged from the ranks of town’s citizenry to get the food to where it was needed most. “We never had a vacant volunteer slot,” Stacey told me. “The other counties that received Sustain and Feed grants had a hard time fielding enough volunteers, so they sometimes had to pay Uber and Lyft to make deliveries. Ridgewood is not only generous; it has a great community spirit!”

As we all know, COVID-19 did not go away any time soon. The Ridgewood initiative received two more rounds of state funding totaling $3.5 million. After nearly three full years of operation, the program ended this past March; tens of thousands of the county’s most vulnerable residents received nutritious, high-quality meals prepared by the area’s best restaurants who, in turn, kept hundreds of their staff employed or partially employed.

“The fact of poverty is not a matter of argument.” “Paterson”

When the shit hits the fan, it doesn’t matter whose raincoat you wear. As Stacey sees it, Ridgewood residents have enormous purchasing power and generally don’t get too agitated by such things as food price inflation. “They realize they’re fortunate. They are also very well educated. It’s an incredible equation for success.” That Ridgewood had the wherewithal and the will to serve dozens of county towns besides themselves should be commended and, frankly, made me feel proud that I was one of its native sons.

But wealth has its privileges which beget more privileges, even when it comes to charity. Paterson, with vastly more human need and a paucity of resources, did not, according to Mary Celis, CEO of the United Way of Passaic County, “have the start-up capital and infrastructure that the state required to be eligible for the Sustain and Feed grant program, even though we have greater need in terms of hunger and small businesses on the margin.” Paterson also has a host of other funding priorities, such as crumbling schools, that Ridgewood’s rich tax base makes it nearly immune to.

Ridgewood raised $100,000 virtually overnight and has a concentration of culinary might second to none in the state. Stacey and her partners merely had to tell the community to “Jump!” and they immediately said, “How high?” Emergencies like COVID bring out the best in people, but they also reveal the system’s failures and the yawning socio-economic gaps that cannot be closed by even the most well-intentioned forms of local charity.

Food, and the lack thereof, is the proverbial canary in the coal mine. When people have less purchasing power and restricted access to healthy food, it stretches their resiliency to the breaking point. We shouldn’t have to wait for a crisis to define the gaps between our communities nor test the limits of their residents’ endurance. Local heroes like Stacey Antine, former Mayor Hache, and Paul Vagianos in Ridgewood, and Mary Celis, Mayor Andre Sayegh, and Deacon Willie Davis in Paterson should be celebrated. Like William Carlos Williams’ man who defied the cholera epidemic, they got their wheelbarrows and brought the food to the people.

But are individual heroics and community spirit sufficient to restore equity to and between American communities? Will those courageous, often selfless actions by themselves bring about the conditions that one day put places like Paterson on some kind of par to places like Ridgewood, or will it, despite the best intentions of people of good will, always be its poor stepchild? Clearly, something stronger, something more systemic are needed to rectify the enormous wealth disparities that exist across this nation and are often most visible between neighboring communities.

One thing I think I learned from growing up in Ridgewood is that neighbors don’t let neighbors suffer. To extend that notion beyond the person next door or down the street to nearby, financially struggling communities, I might turn to Alexander Hamilton, whose footprints are all over Paterson and North Jersey, to say nothing of America’s economic system. Hamilton’s greatest contribution to the new republic was the assumption of the states’ debts by the new Federal government. A more comprehensive assumption of the financial need of under-resourced communities by state governments, progressively funded by their affluent residents and communities, is a form of neighborliness that will distribute economic prosperity to all. And with that prosperity will come, among other benefits, the assurance of food security and access to healthy and affordable food for all.