Five farmers are standing by the side of the road selling their goods at their farmers’ market. It turned out to be one of only two main roads in Colfax, a sleepy little central Louisiana town of 1,600 people cut neatly in half by a railroad track. Nothing too remarkable here as far as Saturday morning markets go – a small number of customers were inspecting the fall fare of collards, squashes, jams and jellies; people were chatting congenially over bushel baskets and pick-up truck beds. As Kate Littlepage, a local farmer and vocational agriculture instructor told me, “This market is less about food and more about community.”

Somewhat more noticeable, at least for this Yankee, was that two of the five farmers were African-American. My racial radar seems like it’s always on these days, but the deeper I plunge into the South, the more blips I see on my screen. It turns out that I was picking up historical signals from the very soil where I was treading. Though the Colfax farmers’ market was micro in size, its racial composition made it out-sized in symbolism. During this week 145 years ago – Easter Sunday, 1873 – over 150 black people were massacred not far from this site by a resurgent force of neo-Confederate, white supremacists that went by the name of the White League, the predecessor to the KKK. Lacking social media and phone cameras, most of America didn’t become aware of the massacre until hand-drawn illustrations appeared in Harper’s Magazine one month later.

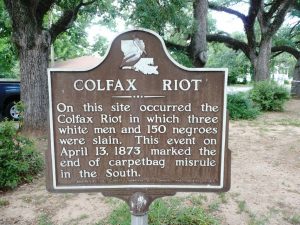

Are the days of racial bloodletting over? In 1950, the year I was born, an unrepentant Louisiana contingent with a dubious historical mission erected a marker in the vicinity of this clash. It read, “Colfax Riot – On this site occurred the Colfax Riot in which three white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873, marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.” It took over 50 years for a more repentant contingent to remove the marker, but it stood all that time as a potent example of the same lies and deceptive messages that are resurgent today.

Calling it a “Riot” instead of a massacre put the blame on a duly constituted, and largely black state militia that was attempting to enforce the newly acquired enfranchisement of black residents. When most of those militiamen surrendered to the heavily armed white paramilitary force, they were gunned down in cold blood. To say that the number of slain “negroes” was 150 is probably a low estimate since many of the bodies were thrown into the nearby Red River, never to be found or identified. “Carpetbag misrule” is a barely concealed Confederate-ism , not unlike “Crooked Hilary,” that undercut Reconstruction’s legitimate task of enforcing federal laws that included protecting the rights of recently freed slaves.

Calling it a “Riot” instead of a massacre put the blame on a duly constituted, and largely black state militia that was attempting to enforce the newly acquired enfranchisement of black residents. When most of those militiamen surrendered to the heavily armed white paramilitary force, they were gunned down in cold blood. To say that the number of slain “negroes” was 150 is probably a low estimate since many of the bodies were thrown into the nearby Red River, never to be found or identified. “Carpetbag misrule” is a barely concealed Confederate-ism , not unlike “Crooked Hilary,” that undercut Reconstruction’s legitimate task of enforcing federal laws that included protecting the rights of recently freed slaves.

Even in a hostile post-Confederate Louisiana, however, federal prosecutors managed to obtain convictions against three of the white attackers. But they would be thrown out by the Supreme Court (United States v. Cruikshank) in 1876 on grounds that enforcement of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments – protection of civil and voting rights – rested with the states, not the federal government. This ruling was effectively the final curtain call for the Reconstruction Era ushering onto the stage one hundred years of Jim Crow.

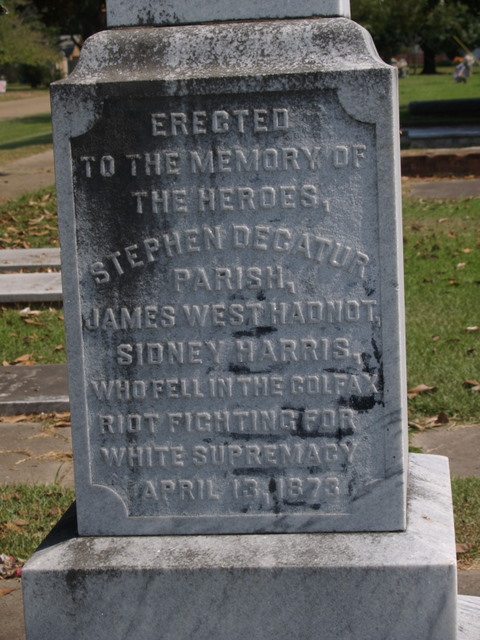

Yale history professor David Blight summarized the Colfax events with a quote in the Lafayette Advertiser (3/7/13): “Colfax is…a case of political murder. It’s murder for political reasons… That’s the kind of society we always say we’re not.” Like the My Lai massacre 50 years ago, when hundreds of Vietnamese civilians were murdered by American soldiers with only one conviction obtained – Lieutenant Calley (he received three-and-a-half years of house arrest before his sentence was commuted to time served); like African-Americans today shot by police for the flimsiest of reasons and whose killers are rarely held accountable; like white supremacists who run down innocent protestors; like this inscription to the three white men killed in the massacre on a 12-foot tall obelisk that stands today in an all-white Colfax cemetery: “In loving remembrance to the memory of the heroes Stephen Decatur Parish, James West Hadnot, Sidney Harris who fell in the Colfax riot fighting for White Supremacy.” The victims are buried and mourned by their loved ones. The perpetrators go free or are memorialized by their community.

If justice is only a dim light on a distant horizon, what do we do in the meantime? Standing by the side of the road with those farmers, not yet fully aware of the meaning of the Colfax massacre, I was reminded of the events that had led up to the opening of this market. They were described to me by James Cotton Dean, Director of Regional Innovation for the Central Louisiana Economic Development Alliance. He has worked in the area for five years, organizing community economic development projects. Dean had reached out to the Colfax community to identify low-cost ways of stimulating the local economy. On one of his first attempts, as he tells it, eight people gathered at a church one night in 2013 to discuss what could be done. Four of them were black and four were white, and each racial group sat separately on opposite sides of the room. Trust was low and the conversation was muted, moving along in fits and starts. After an hour of little or no progress, Dean suggested they take a break.

Dean is young, and at the time was new to organizing work in racially divided communities like Colfax. Worried that the whole evening might be a bust, he was pleasantly surprised when all the people returned to the room. When he asked the group, what was one thing they wanted that they didn’t have, they unanimously replied healthy food. When he followed up by asking what could be done to get healthy food, everyone landed on the idea of a farmers’ market. The rest of the evening was devoted to working out the details of what was to become the Colfax Farmers’ Market. Dean was as shocked as he was relieved when the meeting ended with everyone hugging each other.

I want to find lessons in these stories, but I know that institutional racism in America, whose roots run deep and are watered regularly by white hatred, won’t be undone by local food alone. At the same time, I don’t see a viable pathway without a table where black and white can sit down and break bread with one another. As John Dean said, “Food was something they could do together.” The farmers’ market is only a beginning, a community space, and perhaps the more monuments and markers to racism we tear down the more room we’ll have for good local food.

#StandTogether for racial justice and equality!