“Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested.” Francis Bacon, 17th Century English philosopher

Shelves stuffed with books are supposed to be a symbol of their owner’s intelligence, culture, and a certain savoir faire. Not only is a subjective assessment of your refinement on display, but the quantity and composition of your collection speaks to your values, identity, and idiosyncrasies. They can make an emotional statement as well. After quickly perusing some people’s bookshelves for the first time, I was so excited that I wanted to be their friend for life. On other occasions, I was so appalled I couldn’t find my way to the door fast enough!

of their owner’s intelligence, culture, and a certain savoir faire. Not only is a subjective assessment of your refinement on display, but the quantity and composition of your collection speaks to your values, identity, and idiosyncrasies. They can make an emotional statement as well. After quickly perusing some people’s bookshelves for the first time, I was so excited that I wanted to be their friend for life. On other occasions, I was so appalled I couldn’t find my way to the door fast enough!

My mother’s notion of how an upscale 1950s and 1960s suburban living room should be decorated pivoted around books as much as furniture. The number and right kind of books were not matters to be taken lightly due to the essential role they performed in shaping our status. I can only imagine that there was a “Good Housekeeping” magazine edition of that era with precise recommendations for ratios of bookshelves to total wall space, as well as a curated list of titles that should populate those shelves. For example, five books of poetry (Frost, Keats, D. Thomas, Cummings, and Sandburg), a few volumes of Shakespeare’s “greatest hits,” some Greek and European classics (“Classic,” proclaimed Mark Twain, “A book which people praise and don’t read”), and contemporary fiction that spoke to how au courant you were. “Isn’t he a Negro writer?” one of my mother’s friends inquired with a raised eyebrow as she pulled the James Baldwin novel off the shelf, while another friend would say, “Good for you! You have Ayn Rand!” The copy of Lolita carefully concealed in one dark end of a shelf always evoked a titter or two during my parents’ cocktail parties. And what modern American home would be complete without an encyclopedia—preferably the entire edition rather than just “A” through “H” which was a dead giveaway that you’re buying the entire volume “on time” (I’m convinced I would have got into a better college if “U” through “Z” had arrived before I was 17).

But what does all that say today about me when the most prominent feature of my office is a bookcase stuffed with food and farm books? There’s the anonymous warning found in an ancient Latin text that advises us to “Beware the man of one book!” When I think about today’s extremists, frothing at the mouth over the published pontifications of the latest tech guru, that quote sends chills up my spine. But should we be equally worried about the man of one kind of book? Does having a room where I’m surrounded by nothing but a small sub-genre of non-fiction—one that is as much about bread and butter as it is about how I earned my bread and butter—suggest that I’m one-dimensional?

To be honest, my living room is largely given over to books as well, though you will find nary a food or farm book there. I once tried to change that, but to ill effect. In the interest of applying an inter-disciplinary approach to interior design, I integrated many food books from my office into my living room. My thinking was that diversity of topics and perspectives would be healthy for everyone. Wrong! Soon, I heard rumblings coming from the living room late at night, even expletive-laced directives as to where to stick “your English cucumber, foodie!” I thought I was dreaming until I found books scattered across the floor the next morning. The noises grew louder and angrier night after night; the cracking of spines and ripping of pages were audible, and shredded jackets of a dozen or more books were ground into the carpet. When terrible things about Shakespeare’s mother were scrawled on the Bard’s play covers, I’d had enough. Gang warfare had erupted! I halted my experiment with genre diversity and returned my food books to the office.

Since my books have agreed to a forced armistice, I can enjoy my food and farm titles for the tales they tell, about my evolution as well as that of the food movement. Dropping back nearly 50 years, there were two books that captured my attention as a just-out-of-college kid trying to align my moral compass with the need to make a living. Food For People by Catherine Lerza and Michael Jacobson (1975), my copy now yellowed and duct-taped, was so far ahead of its time with respect to hunger, nutrition and health, and food production that we’re still trying to catch up. Radical Agriculture, edited by Richard Merrill with essays by Wendell Berry, Jim Hightower, and Michael Perelman (1976) synthesized the work of such forebearers as Robert Rodale and began the task of swinging the lumbering ship of conventional farming to the more abiding shores of organic, sustainable, and regenerative.

Since my books have agreed to a forced armistice, I can enjoy my food and farm titles for the tales they tell, about my evolution as well as that of the food movement. Dropping back nearly 50 years, there were two books that captured my attention as a just-out-of-college kid trying to align my moral compass with the need to make a living. Food For People by Catherine Lerza and Michael Jacobson (1975), my copy now yellowed and duct-taped, was so far ahead of its time with respect to hunger, nutrition and health, and food production that we’re still trying to catch up. Radical Agriculture, edited by Richard Merrill with essays by Wendell Berry, Jim Hightower, and Michael Perelman (1976) synthesized the work of such forebearers as Robert Rodale and began the task of swinging the lumbering ship of conventional farming to the more abiding shores of organic, sustainable, and regenerative.

But as I’ve heard Jim Hightower say on several occasions, “While it may be the rooster who crows, the hen delivers the goods,” I also include Joan Dye Gussow’s and Jan Poppendieck’s books among my first influencers. Gussow’s Chicken Little, Tomato Sauce, and Agriculture (1991) became a part of the early warning system that alerted us to how food production was becoming “de-natured” and our food system was blindly falling under the spell of science and technology. Poppendieck’s Sweet Charity? (1998) pulled the bandages off the bourgeoning food banking and emergency food world to reveal that bandages weren’t enough. Together, these two volumes sharpened my analysis of the perils associated with prevailing but non-systemic solutions. The result was a renewed resolve to engage public policy and grass-roots food activism.

Apart from that first round of tomes that ignited a fire under this would-be food system reformer, there were a category of mostly 21st century pubs that either sharpened my analysis or softened my heart. Among the former of course was Michael Pollan’s In Defense of Food (2008) whose distillation of his seminal food reporting and the holy bible of the food movement, Omnivore’s Dilemma, enlivened our food consciousness for a good long while. (Against my better instincts, I loaned out my copy of Omnivore’s which, of course, was never returned. Book kidnapper, you know who you are! Your soul and those of your children will never be at ease until you return my book!).

School Food Revolution (2008) by Kevin Morgan  and Roberta Sonnino built a framework for the fast-emerging farm to school and good-food-in-schools movement. The book’s title is perhaps one of the more accurate in the food issues sub-genre often known for its hyperbolic titles. Given that the change over the last 20 years in school food has been nothing less than spectacular, Morgan and Sonnino nailed it.

and Roberta Sonnino built a framework for the fast-emerging farm to school and good-food-in-schools movement. The book’s title is perhaps one of the more accurate in the food issues sub-genre often known for its hyperbolic titles. Given that the change over the last 20 years in school food has been nothing less than spectacular, Morgan and Sonnino nailed it.

Less granular, perhaps, but more spiritually uplifting are three books on my shelf whose author’s words touched me when and where I needed it most. The Seasons on Henry’s Farm (2009) by Terra Brockman and Food and Faith (2011) by Norman Wirzba, both gave me reasons to believe in my work when my hope was at a low ebb. Stanley Crawford, author of The Garlic Testament and Mayordomo, passed away this winter leaving the hills of Northern New Mexico and the Santa Fe Farmers’ Market grieving the loss of his gentle presence. But Stan’s books will inspire and instruct for decades to come (pictured here is The Garlic Papers (2019) since the same person who “borrowed” Omnivore’s Dilemma probably has my copies of Crawford’s other work as well. Second warning: charges against you may be upgraded to a felony).

Contrary to my mother’s thinking, having a large number of books doesn’t necessarily make you a good person. Hitler supposedly owned 16,000 books while Stalin’s collection topped out at 25,000 (The New Yorker, 2/26/24). I heard a mid-list author once say, “I own 1,000 books, but 900 of them are mine.” Apparently, his publisher offered him his unsold editions as an option to dumping them into the remainder pile. My shelves only store a modest number of my own books, which I keep in inventory pending the day when their rarity drives the price through the roof. A more likely scenario, however, is when I had to use eight copies of Stand Together or Starve Alone* to hold my office door open during a particularly hot and windy summer day. Upon seeing this, my son couldn’t help but crack, “Finally, Dad, your books are being put to good use.”

Though nothing beats the thrill of having your own book placed in print for the whole world to fondle, a close second is helping a would-be author realize their dream. That’s why writing a forward or an endorsement for another’s book, or even helping a colleague through the complicated writing and publishing process can sometimes be a joy. I say “sometimes” because the food book sub-genre, like the food system itself, has generated its share of “waste.” There are too many people who fashioned themselves as writers who, frankly, should have never strayed from their day jobs. But for those who have both the itch and the ink to pull it off, I’ve had fun playing a small midwifery role.

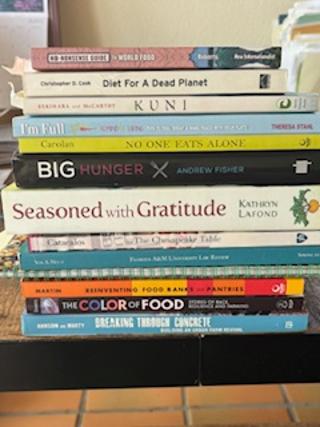

To that end, I pulled more than a dozen books off my shelf whose creation I’m proud to have been associated with, even if it was just as a reviewer. One in particular is Breaking Through Concrete (2012) by Edwin Marty and David Hanson (forward by Mark Winne) that speaks to the beauty and excitement of urban farming that’s taking back real estate at both the city core and urban fringe. The Color of Food (2015) by Natasha Bowens (I advised and endorsed) was an early entry into the often-overlooked field of how people of color are (and have been for a long time) staking a claim to land to make what magic they can from its soil. Like Breaking Through Concrete, it’s a story told with robust words and beautiful photographs. And an old hometown favorite is Reinventing Food Banks and Pantries (2021) by Katie Martin (I advised, coached, and connected), a former intern of mine during my days in Hartford, Connecticut. Reinventing does just that by bringing fresh ideas and new juice to an emergency food system that had become brittle and dry.

To that end, I pulled more than a dozen books off my shelf whose creation I’m proud to have been associated with, even if it was just as a reviewer. One in particular is Breaking Through Concrete (2012) by Edwin Marty and David Hanson (forward by Mark Winne) that speaks to the beauty and excitement of urban farming that’s taking back real estate at both the city core and urban fringe. The Color of Food (2015) by Natasha Bowens (I advised and endorsed) was an early entry into the often-overlooked field of how people of color are (and have been for a long time) staking a claim to land to make what magic they can from its soil. Like Breaking Through Concrete, it’s a story told with robust words and beautiful photographs. And an old hometown favorite is Reinventing Food Banks and Pantries (2021) by Katie Martin (I advised, coached, and connected), a former intern of mine during my days in Hartford, Connecticut. Reinventing does just that by bringing fresh ideas and new juice to an emergency food system that had become brittle and dry.

In my third book Stand Together or Starve Alone* (now in paperback and available directly from me or Amazon*) I identified the growth in published food issue books since 2005. Even I was astounded by the numbers. Limiting my search to categories like hunger and food insecurity, sustainable agriculture, and food systems (this leaves out large swathes of topics like health and nutrition, cookbooks, and garden books), the number of published titles grew four to sevenfold in ten years:

Food Systems: 2005 – 52 titles; 2015 – 372 titles

Hunger and Food Security: 2005 – 148 titles; 2015 – 929 titles;

Food Policy: 2005 – 53 titles; 2015 – 241 titles

I and other food authors have benefitted from this rising tide of attention as much as we have sometimes been diluted by the tsunami of titles. Yes, at times it does appear to be too much, especially when one sub-genre of food books would divide and sub-divide again into a reductionist pile of crumbs. But for the most part, our world’s food, health, political, social, economic, racial, and environmental knowledge has been leavened like a beautiful souffle by the onslaught of literature that sparkles with every facet of our sustenance. Our book shelves may be embarrassingly overweighted with food titles, but at least they are conversing amicably, sharing information openly, and on their best days, advancing a more unified view of the food system universe.

*If you want to purchase the paperback version of “Stand Together or Starve Alone” directly from me for $20 including shipping, send me an email at win5m@aol.com. Also available on Amazon: Amazon.com: Stand Together or Starve Alone: Unity and Chaos in the U.S. Food Movement: 9781440844478: Winne, Mark, Palmer, Anne: Books.

I LOVE what you are all about,Mark. It’s obviously all from the heart. Food books are at the core of how we nourish our souls. What is more important?